NAND Flas as a technology are always in the spotlight, and it just so happens that they are currently in an increasing number of devices in the world. For this reason, it is normal that now this market is so volatile in its prices, where in addition each new stacking technology shakes the foundations for the rest of the manufacturers that do not have it. A clear example has been the new QLC , which is being implemented in an increasing number of SSDs, but which has not yet finished taking off. Is it really the future? Is it profitable and is it worth it?

Like all NAND Flash, these are based in turn on memory cell technology, which have had a great evolution as architecture since their first electronic circuits and although we are not going to explain in depth how they work or what their history is, yes. We will give a brief review to focus on the news of the QLC as such.

Why Choose NAND Flash Over Common RAM Chips

One of the paradoxes of SSD vs system RAM is that although the former are slower, less dense and more expensive to manufacture than the latter, it is the case that the technologies and the approach for which they are designed separate them completely, although its principles are the same in reality.

The main difference is that NAND Flash as a technology is based on FGMOS or floating-gate MOSFETs , which are a type of metallic semiconductor field effect type transistor. This implies that the Gate as such is isolated and has direct current, which is the basis of the technology for an SSD: The objective is that each cell maintains its electrical tightness, thus allowing the data that is stored to be saved.

RAM does not work like that, but being of the MNV type or non-volatile memory, it always needs a current to flow through it, so its architecture is based on MOS capacitors. Therefore, the SSD seeks to store each bit of information so that the controller, the CPU or the GPU can access it and read each cell based on 0 and 1.

Therefore, and of course, the first NAND Flash cells started by being able to store 1 bit each in two different states (zero and one). This type of NAND Flash memory was called SLC or Single Level Cell and it is the basis of any old or current SSD, although with many nuances along the way.

A change of trend in the sector with QLC

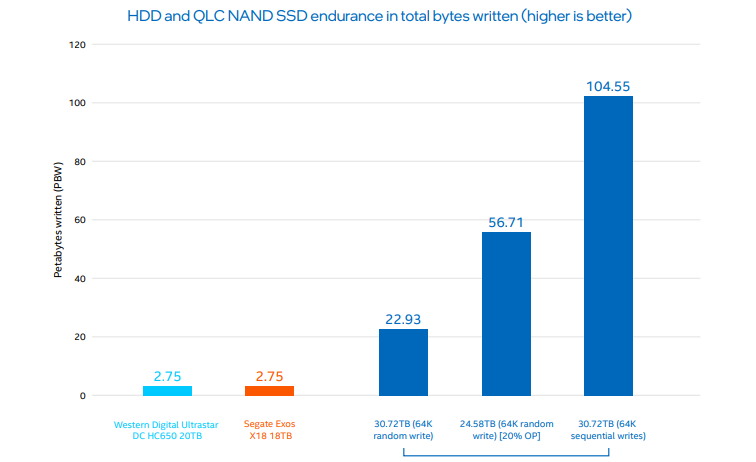

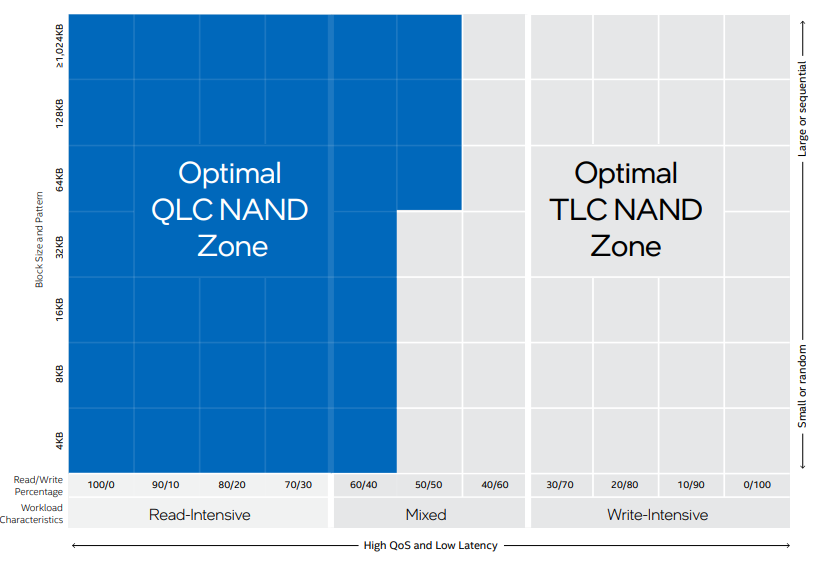

The premise for switching technology is simple, but it comes with some problems and benefits at the same time. What the storage industry wants is to increase the capacity of these devices as a main objective, but behind that there is for example the speed, the price per GB included and of course the durability.

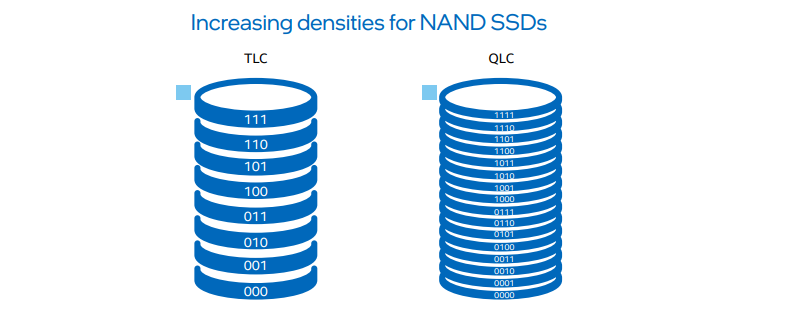

Here is all the controversy, so we are going to explain everything about QLC memories so that it is understood. As we have already guessed, the QLCs are fourth level or Quad Level Cell memories and they start from the premise that they are based on the technology introduced with their predecessors, the TLC.

These types of third-level memories achieve similar performance to MLCs today but with shorter life cycles, usually and on average between 3000 to 5000 cycles per cell. This means reducing its useful life, but due to its new structure they manage to lower the price per GB, so as the durability is acceptable for more than 10 years seen in a consumer SSD, it is a valid and very balanced technology in all aspects. .

From SLC to MLC, TLC and now QLC, what’s new as a technology?

With QLC the industry manages to increase the capacity, but also the complexity and durability of each cell. You get 4 bits per cell, but up to 16 different voltages must be implemented, one for each state for the number of bits that are contained. Therefore, this amount of states and voltages cause a loss of reading speed and especially writing on an SSD.

The validation and checking of each bit is also more complex and each cell degrades much more, so even the common ECC is not enough to maintain structural integrity and other error checking methods had to be resorted to. Logically, if we have to resort to all this, the internal read and write cycles are higher (not to be confused with the external data transfer cycles themselves) which has an impact on a total useful life of between 500 to 1500 erasing, writing cycles and reading.

Therefore, the use of SLC caches has become necessary to increase the performance of these SSDs to levels of at least TLC. Ergo, as the industry moves up the notch with the highest number of bits per cell, speed and durability go down at the cost of capacity and that’s where the whole problem lies.

The market tries to move to QLC, but for the moment neither the costs are lower if we compare SSD models TLC vs QLC in themselves, nor the advantages outweigh the disadvantages at the moment.

It is true that there are models where the optimal circumstances are taking place to affirm that QLC is the same or better, but they are niche models where users are placing trust and this generates a greater volume of chips and therefore lower cost.

But then why choose QLC over a good SSD with TLC? Mainly due to capacity and costs. Each time SSD comes out at a lower price per GB with increasingly higher yields and with greater capacity, so it is only a matter of time that TLC remains marginal in the market. Likewise, with QLC a new type of NAND Flash called X-NAND is being given that paradoxically can snatch the throne of the industry from the first, since it covers part of the problems inherent to this technology and that at the same time maintains the standards of cell levels, so you could start with QLC and move on with PLC with no problems.

The future of QLC is promising, slow yes, but the industry increasingly lengthens the GAP between new levels, which allows the technology to mature and the manufacturers to compete. PLC will be its successor and although there are great strides with it, it really is still far in the market to see high performance consumer SSDs in generous capacities at competitive prices.